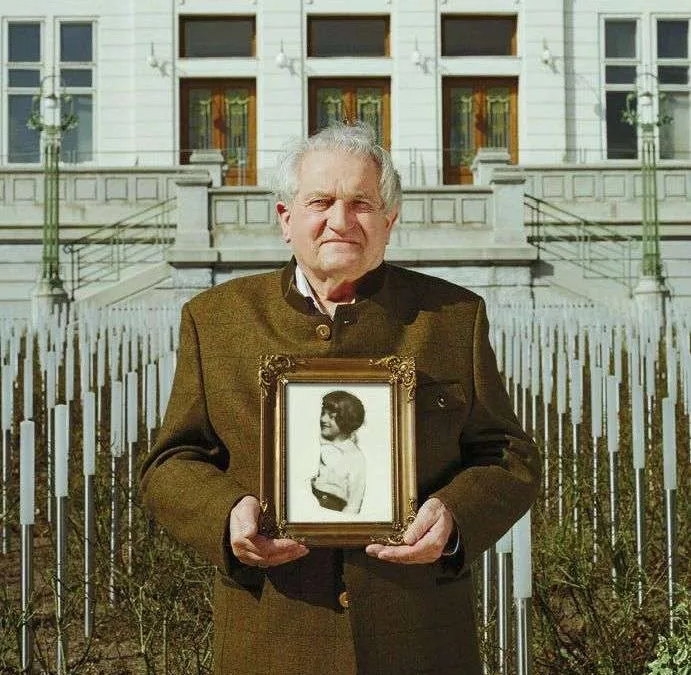

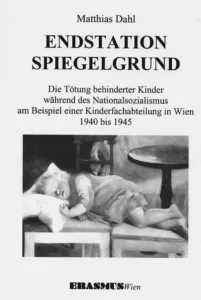

Rudolf Karger was born on July 16, 1930 in Vienna. From September 1941 to September 1942 he was in the notorious children’s institution Am Spiegelgrund, established in July 1940 on the grounds of the “Am Steinhof” sanatorium and nursing home in Vienna. By 1945, as part of the National Socialist “child euthanasia” program, nearly 800 sick or mentally impaired children were murdered there. Afterwards he was sent to Mödling, to the former Hyrtl’sche Orphanage, a Nazi re-education institution, where children were indoctrinated with Nazi ideology using the most brutal methods.

I was born on July 16, 1930 in Vienna and grew up in Ottakring in a municipal apartment consisting of one room, a small chamber, and a kitchen with cold water supply. Usually twelve people lived there, four of them children. Of the eight adults, only three were generally employed; the others were without work, unemployed. It was not a good time.

When German troops marched into our beautiful Austria on March 12, 1938, with great celebration and fanfare, it was no day of joy for me and my family. First, on the night of March 12, one of my uncles was taken from our apartment and sent to the Dachau concentration camp, because a few days before the German troops marched in he had dared to say in front of others: “Who needs A. H. [1] in Austria?” He was denounced [2] and spent two years in Dachau for it.

My two older sisters, Alice (born 1929) and Elfi (born 1927), and I were born out of wedlock, which at that time was still considered a disgrace. Our mother had already died in 1936 at the age of 29, when I was six years old, and our father was not present for us children. When my sister Elfi was born in 1927, my father was only 16 and my mother 19. For whatever reason, my father was unwanted by my mother’s family, and my mother was unwanted by my father’s family. So I grew up with my two sisters without parents. My maternal grandmother was our legal guardian, but since we were born out of wedlock, our official guardian was the Youth Welfare Office. In 1938, the Youth Welfare Office was declared part of the Reich Youth Office, and we three children were unwanted by the Nazi regime, even though we were neither mentally nor physically disabled.

It was compulsory to participate in the “Deutsches Jungvolk” [3], but I stayed away. One day, in Thaliastraße, a column of Hitler Youth marched past me with the German flag at the front. At eleven years old, I did not think to greet the flag with an outstretched arm. The leader immediately stepped out of the column and gave me two heavy slaps in the face for not saluting. Once, after 9 p.m., the police picked me up while I was on my way home, because even at ten years old I liked going to the theater. That earned me more slaps, and my grandmother had to fetch me late at night from the police station. Several times I spent the night asleep on the staircase when my uncle was at home. I was very afraid of him, because he beat me violently without reason. So I would wait on the floor until he left again in the morning. All this was reported about me to the Reich Youth Office — were these the reasons I was sent to Spiegelgrund?

So my guardianship — the Reich Youth Office — cleared the way for me to be committed to the children’s institution “Am Spiegelgrund”! There, A. H.’s doctors and helpers carried out his party program to annihilate everything not worthy of his “Greater German Reich.” His helpers skillfully showed their willingness to torment us boys and girls. We had to endure suffering and always be prepared to die.

On September 1, 1941, at the age of eleven, I was transferred from the Children’s Reception Center in Vienna’s 9th district, Lustkandlgasse, to Spiegelgrund. September 1 was a beautiful autumn day. I don’t know to which pavilion I was taken — either Pavilion 7 or 9. From the outside they all looked the same: brick buildings, just as they still exist today. When I was led into the pavilion, it was empty. I was able to look around to see where I had landed. The doors were locked and the windows barred. The pavilion had a long corridor, a day room, a bathing room with showers, a large dormitory with about 25 beds, a small kitchenette, and a duty room — all kept immaculately clean. Around 4 p.m. I heard loud voices, and when the door opened about 25 boys my age entered, accompanied by two nurses who seemed friendly at first. But the next day I already realized they were very brutal with us.

Much is already known today about the cruelties inflicted on us. Still, I would like to describe some of the suffering I personally experienced:

Slaps in the face came daily. Night after night we had to stand by our beds wearing only our nightshirts, which reached to our knees — in summer with the windows shut, in winter with the windows open.

Forced marches. Once even to the police station at Praterstern. One of us had escaped, and we had to fetch him back. Spiegelgrund–Praterstern and back, Praterstern–Spiegelgrund. When we all arrived back at Spiegelgrund, we were utterly exhausted from fatigue. The anger was directed at the fugitive, whom we had to return. Friendships among us boys never existed. We were “trained to be hostile toward each other,” and whenever punishment was given, we were told we could “thank him for that.”

Once a week we were served semolina porridge for lunch, but not made with whole milk, butter, and chocolate. No, it was thin, made with skim milk, with lumps. We had to eat it. One boy could never manage it. Two nurses held his nose and forced it down his throat. He vomited it back onto the plate every time, and the procedure repeated until the plate was empty and he had swallowed it all. Meanwhile we had to stand and watch the torment.

Then came the notorious vomiting injections, which made us vomit and suffer great pain. When Dr. Heinrich Gross [4] was questioned about this in his trial [5], he casually explained it was harmless — only meant to keep us from becoming arrogant.

In 1941, I also experienced Christmas Day with the whole group. In the day room, a Christmas tree was set up with nothing on it, and we had to stand before it for hours as punishment, without moving. That was my — our — Christmas Eve. There was nothing sacred, no presents.

Punishment by standing for hours was routine. Day after day.

Once a month my grandmother was allowed to visit me briefly. In my presence, they always explained to her how well they were caring for us. As if the only thing they had not done was to kill us. I never told my grandmother what they really did to us, the pain and suffering they inflicted. If I had, she might have gone to the director to complain, and then she too might have been sent to a camp.

On one outing I had the chance to escape. Homesick, I ran back to my grandmother’s. Less than two hours later, the doorbell rang. Two nurses from Spiegelgrund were already there to take me back. They assured my grandmother it would have no consequences for me. But I knew what awaited me — as with all who had tried to flee. And I was not spared. Back at Spiegelgrund, I was slapped so hard I thought I would go deaf. At the window stood the whole group, silent, being punished by standing. My clothes were torn from me, and in front of the group — as a deterrent — my head was shaved. Not clipped, but more like torn out with scissors. Bloody and scratched, I was then dragged into the bathroom. The tub of cold water was ready for me. I was shoved in and dunked many times until I could hardly breathe, gasping, swallowing water, struggling. In despair I pulled the plug out of the tub. They dragged me out and put me under a cold shower for fifteen minutes. It was terrible — I could barely move when I was pushed out into the corridor. Crawling on my knees, I had to pass through a gauntlet of beatings. Then they pulled a nightshirt over me and sent me to Ward 15 or 17, the pavilions where death was a daily occurrence.

I remember vaguely being locked in a cell, very hungry, given painful injections. I saw only men and women in white coats who were not kind to me. I don’t know how long I was in Pavilion 15 or 17. Today I know it was the clinic of Dr. Gross, who took brains from tortured children for his research. I believe I was spared only because my brain was not considered suitable for him. Afterwards I was sent to Pavilion 11, the punishment ward. About 20 of us boys were there — those who had fallen into disgrace, regarded as even worse than those in Pavilions 7 or 9. The punishment was the same. The only difference: there were no female nurses, only male orderlies. I especially remember we had to rip open beds repeatedly and then make them again so that the sheets were aligned to the millimeter.

I had been at Spiegelgrund for a year when suddenly, on September 4, 1942, I was transferred with around 70–90 boys to the Nazi re-education home in Mödling. It was the former Hyrtl’sche Orphanage, converted into a Nazi training home for us “bad children”! We were subjected to military drill and brainwashing. We had to memorize everything — under strict punishment if we forgot — about A. H. and his political program for the “Thousand-Year Reich.”

On July 7, 1943, I was finally allowed to return to my grandmother, who always strove to bring us three children back home.

This time and my suffering at Spiegelgrund live on in me as if it had happened only yesterday, not 69 years ago. Life at Spiegelgrund was inhuman, and reports at the time even sugarcoated it. We were used as “guinea pigs”: different injections to test medicines, forced cold showers, in winter wrapped in wet blankets, and much more. This one year of painful life at Spiegelgrund destroyed my childhood, my youth, and my future.

It was also cruel because my education was blocked. There was no school. Marked by Spiegelgrund, I stood without a chance for the future. The one-time compensation […] from the Austrian National Fund cannot come close to making up for what was done to me. I was no genius, but neither a fool. Yet through my time at Spiegelgrund I was robbed of the chance to be better positioned for the future. Professionally and financially I remained disadvantaged.

As a witness to history, I sometimes speak in schools about the atrocities committed against us children and adolescents during the Nazi era. The time at Spiegelgrund brought us suffering, pain, and death. We were unwanted by the regime — inferior, unworthy of life. And I find it very good when people work hard to ensure that these crimes of the Nazi era are never forgotten and are exposed.

For my work as a witness to history, I was honored by the City of Vienna with the Golden Decoration of Merit.

Rudolf Karger died on January 30, 2015.

I share stories like Rudolf Karger’s because remembering history shapes how we value children today. My own work focuses on parenting and child development, translating science into tools for families. If you’d like to explore my science-based parenting course, you can find more here. Join my newsletter here.

The first publication of this article appeared in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism (ed.): Memories. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism. Vienna, 2010, pp. 206–212.